Wyoming working together

The story of the Wyoming Range Legacy Act

There are times, even at a large gathering, where it seems as if there are only a couple of people in the room. People who matter, anyway.

A warm day in mid-September 2007 was like that as five people hopped into a pickup in Pinedale, Wyo., and headed to the crest of the Wyoming Range, a place called McDougall Gap. At the wheel was Duane Hyde, a tall, graying cowboy turned game warden, recently retired. Riding shotgun was freshly-minted United States Republican U.S. Sen. John Barrasso. Those in the back seat were just passengers—and witnesses—in every sense of the word.

A Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout taken from one of many streams within the Wyoming Range.

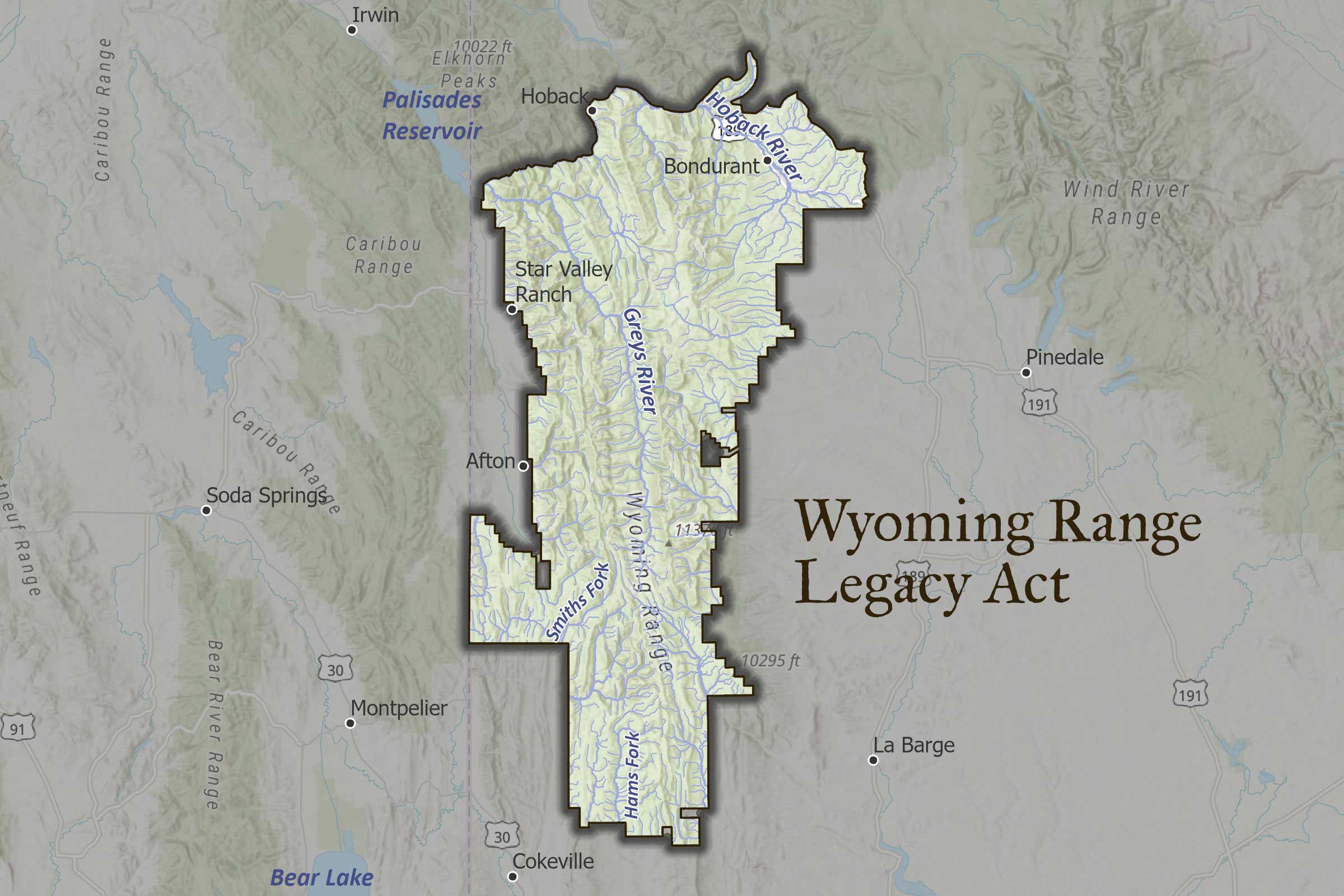

Hyde, who had spent a lifetime in and around the Wyoming and Salt River Ranges first as a child growing up in Star Valley and then as Wyoming’s most senior game warden wearing the fabled badge number one, was serving as the face and voice for a group called Sportsmen for the Wyoming Range, a group started, led and funded by Trout Unlimited. Barrasso had just been appointed by Democratic Gov. Dave Freudenthal to fill some very large boots, those of Republican Sen. Craig Thomas, who had passed away earlier that summer. Freudenthal had made protecting the Wyoming Range a critical issue for the candidates vying to fill Thomas’ vacated footwear, and it was Barrasso who expressed the most willingness to do so. Hyde and a host of other Wyoming citizens from all walks of life and all political persuasions wanted a special piece of high country—collectively called the Wyoming Range—protected from future oil and gas development. The protection they wanted included all of the Bridger-Teton National Forest sprawling across several mountain ranges and three forest ranger districts.

When I was appointed to the U.S. Senate, I made introducing Wyoming Range legislation a top priority. One of the biggest supporters of this legislation was Trout Unlimited. The Wyoming Range embodies the heart and soul of Wyoming. It’s home to splendid natural landscapes that attract tourists, recreationalists, hunters and fishermen alike. It was wonderful to work side by side with members of Trout Unlimited to make sure the Wyoming Range’s pristine landscapes will be protected, preserved and passed down to future generations.

—U.S. Sen. John Barrasso, Republican, Wyoming

As Hyde drove, he mostly listened. Barrasso, like many in Wyoming, had never been into the Wyoming Range and he wanted to see it with his own eyes. Pinedale was hopping with hunters and anglers heading out into the surrounding mountains and gas field workers heading out onto the nearby sagebrush mesa called the Anticline, where one of the country’s biggest gas booms was going great guns. Hyde steered past drill rigs and rig workers, and turned up a washboarded road west, through Bureau of Land Management ground, pausing to let a group of sage chickens cross the road. Pronghorn barked and galloped off. Then they were on the forest, the road climbing. At McDougall Gap, they stopped and got out and enjoyed a brilliant fall day in the high country, their backs to the drainage they had just climbed—home to native Colorado River cutthroat trout—and looking into the Greys River drainage, where pure Snake River cutthroat swam. Hyde was quiet. He wanted the land itself to do the talking. It did.

The Wyoming Range Legacy Act protected 1.2 million acres of forest from new gas drilling. Two of the people most instrumental in making it happen were Senator John Barrasso (left) and retired game warden Duane Hyde, leader of the Sportsmen for the Wyoming Range, a coalition started by Trout Unlimited.

A month later, Wyoming’s new Senator introduced to the U.S. Congress his first piece of legislation, the Wyoming Range Legacy Act, a bill unlike any other in the country for its scope and scale and, ultimately, its fairness. An early draft of the bill had been crafted by Thomas and his staff, many of whom had stayed on after their boss had died. Trout Unlimited staff, which was the driving force behind Sportsmen for the Wyoming Range, wrote major portions of the bill. Ultimately, it protected 1.2 million acres of the forest from new gas drilling and allowed for the buy-out of gas leases that were valid but not yet developed. Roughly 120,000 acres of undeveloped leases existed in the range.

The trip that beautiful September day truly represented a mid-point for what is now recognized as one of the most vigorous, nonpartisan and successful grassroots conservation movements ever undertaken in the country’s recent history. Those who worked on and supported the Wyoming Range Legacy Act had been at it for years and that day in 2007 was just a marker. Like a mountain pass, one still had to drop down the other side. Two more years were needed to entice two slow-moving Congresses and an entirely different President from an entirely different party to pass and sign the act into law.

Roosevelt Meadows, deep in the Wyoming Range, was visited by the late Senator Craig Thomas just before he wrote legislation that would be his legacy.

Climbing the hill had been arduous. Thomas had ridden horseback into the range at the behest of area residents back in 2004. Those locals were a loose coalition of homeowners in a subdivision on the northeastern end of range called Hoback Ranches and others who lived on the Upper Hoback River. Later the group officially formed as Citizens Protecting the Wyoming Range and got a considerable boost when a seasoned big game outfitter named Gary Amerine stepped to the lead.

Amerine, like Hyde, was a real-deal, homegrown face and voice of grassroots interests who saw the need for protection of the range. Possible gas development on 44,720 acres of national forest directly west of his home outside Daniel Junction spurred him into action. Amerine and his neighbors recognized the importance of the gas boom to the economy, but they also wanted to save a piece of Wyoming for future generations. Sen. Thomas felt that way as well, penning a letter to his fellow Sens. Jeff Bingaman and Pete Domenici who sat on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

The Wyoming Range

“Wyoming is certainly doing its part to supply the nation with energy,” wrote Thomas after congratulating the two New Mexico Senators for passing a mineral withdrawal bill on stunning public lands called the Valle Vidal that protected a storied trophy elk herd. That withdrawal was just over 100,000 acres in size. Thomas had something more than ten times that size in mind.

A poster child of the movement was an exploratory gas well, ultimately not viable, that was drilled on the banks of a native trout stream called Fish Creek within eyeshot of the bighorn sheep on Darby Mountain deep in the range. Sportsmen for the Wyoming Range, recognizing the critical importance of the range for wildlife and fisheries habitat, was formed with a motto: “We’re Mother Nature’s Bodyguards and Yes, We’re Heavily Armed,” which eventually found its way onto billboards across the state, paid for by a Trout Unlimited donor. For anglers and hunters, the range was renowned for its trophy mule deer, elk, sheep and moose habitat and its fishing—there is no Wyoming Cuttslam without the Wyoming Range (the Cuttslam is achieved when an angler catches one of each of the four native trout in the state). But even if one didn’t hunt and fish at all, there was a wide recognition among residents of Sublette and Lincoln counties—the locals—that the range was something special that needed protection. That feeling soon washed across the state.

Protection was the critical word and it applied not only to conservation of pristine land, but also security for private property rights like valid oil and gas leases. “We will pay you not to develop your leases” was the mantra of the proponents of the act. This, ultimately, made the effort palatable for many, including some oil and gas companies like Houston-based Plains Exploration (PXP) which held nearly 60,000 acres of leases in the Hoback Basin and Cliff Creek within the proposed boundary of the withdrawal.

“The key to the success of the Wyoming Range Legacy Act was the fact it revolved around the concept of willing sellers and buyers as opposed to a government-imposed mandate or restriction of vested rights,” said Steve Rusch, who retired as vice president of government affairs for PXP. “This approach fostered communication and collaboration between different stakeholders as opposed to cementing lines of opposition.”

A release of a Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout into a Wyoming Range stream.

After Barrasso introduced his legislation in October 2007, the real work began and it was a model for Trout Unlimited’s advocacy work that went hand-in-hand with grassroots, staff and leadership. It was a blueprint of people working together regardless of how they felt about Washington and local politics. Democrat Freudenthal and Republican Barrasso were the tip of the spear, but this was only the beginning. Trout Unlimited took staff of Sen. Mike Enzi on horseback into the range. Members of a Pennsylvania chapter of Trout Unlimited who had come to the Wyoming Range to catch the fabled Wyoming Cuttslam, pushed their Republican Sen. Arlen Specter—a critical vote—to support the bill. Amerine enticed one of his former hunting clients who worked as a guard in a federal prison in a critical eastern state to travel to DC to lobby his representatives and a national trustee for Trout Unlimited who had grown up with Tennessee Republican Sen. Bob Corker made a key visit to his old pal. Trout Unlimited met with Vice President Dick Cheney’s office to talk about fishing, the Cuttslam and Wyoming native Cheney’s love of fly fishing in places like the Wyoming Range. Enzi, too, was a fisherman with the love of places like the Greys River.

Here’s the caption

The act joined people who might not ever willingly break bread together. Deeply conservative men like Hyde, Amerine, Barrasso and the billionaire ranch owner and Trout Unlimited donor Joe Ricketts, found common ground with environmental groups and representatives of the other side of the legendary “aisle.” Union trona miners in Sweetwater County joined with conservative outfitters. Endorsements were secured from such varied groups as the Wyoming Outfitters and Guides Association, the Wyoming Wildlife Federation, the Wyoming Game Wardens Association, the AFL-CIO (and some 60 unions), the Mule Deer Foundation, the National Outdoor Leadership School, and an organization representing Wyoming’s faith community, among many more. The Wyoming Game and Fish Commission gave a nod of approval. Gas field workers, who made a living on the Anticline but camped with their families on Wyoming Range streambanks in the summer and hunted its high country in the fall, stepped forward. A few went to Washington. One famously quipped, “I don’t want to smell my job when I’m on vacation with my family.” Even the aforementioned gas company, PXP, lobbied in support behind the scenes with a critical conservative Democratic Senator, among others.

After the 2008 election, a new Congress took up the act and other conservation bills across the country and lumped them all together into a bill called the Omnibus Public Lands Act of 2009. The conservation, citizens and angler/hunter groups all walked the marble hallways in DC. A staff member of Trout Unlimited wrote testimony for a hearing in the Senate that Gary Amerine artfully delivered after setting his dress Stetson down on the table beside him. The bill passed and finally, on March 30, 2009, the Wyoming Range Legacy Act became law with the signature of President Barack Obama.

Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout.

Buy-out

The sportsmen and citizens groups had achieved their ultimate mission and disbanded, but a critical piece of the puzzle, the Hoback Basin, was still able to be developed under the law. This basin was recognized as one of the most important pieces of habitat in the entire range, particularly for migrating mule deer and moose. Residents of the area gathered members with a mission of preventing drilling in the Hoback with the hopes of buying out PXP and retiring those leases forever, as the new law allowed. After a long back-and-forth between the company and the citizens group, an agreement to sell was finally reached in 2012. The non-profit Trust for Public Lands, acting on behalf of thousands of Wyoming citizens and others who had donated the $8.75 million for the buy-out, purchased the leases from PXP and turned them over to the federal government for permanent retirement. A good portion of the purchase price came from the billionaire conservation philanthropists Hansjörg Wyss and Joe Ricketts, but some $2 million was raised by more than 1,000 individual donors. Sadly, neither Thomas nor Hyde, who died of a heart attack in the summer of 2009 while spraying weeds on his Star Valley Ranch, lived to see the result.

“In the end we were able to craft a win-win solution for all parties and accomplish something notable for future generations,” said Rusch. “Through the collaboration that ensued between PXP and the sportsmen’s groups, all the parties had an opportunity to better learn and appreciate each other’s concerns.”

Lastly, in the final hours of the Obama Administration, another 21,000 acres of leases that had been contested for years by citizens, sportsmen, conservation groups and others, were deemed invalid while TPL purchased an adjoining 23,000 acres of valid leases and retired them. This was the very country on Horse Creek west of Daniel Junction that had fired up conservative sportsmen like Gary Amerine and many others.

—Tom Reed, Pony, Montana

TROUT PEOPLE

Scott Stouder

Scott Stouder had an epiphany. It can only be described that way, for the word describes a life’s alteration, a sea change. He was covered in sawdust and swallowed in the bottomless silence that follows the crash of a big tree thundering to the ground and the thumbing of the “off” switch on a chainsaw. Stouder, who had grown up in a logging family and spent a lifetime from boyhood to manhood felling timber all over the Northwest and Alaska, literally put down his saw for the last time on that day many years ago, thinking, “I don’t want to do this anymore.”

Everything he had done in his life came to this moment, a life spent outside running equipment in the forests and free time in those same forests with a rod and a rifle. That day, Stouder walked out of those woods and into a second career in outdoor writing and then a third career in conservation told through the lens of the sportsman.

In 2004, after coming to the attention of Chris Wood at Trout Unlimited because of his outdoor writing ability, Stouder joined a small but talented group of fellow angler/hunter conservationists as a full time employee, based in Idaho. This was the very beginning of Trout Unlimited’s work to protect public lands.

Right from the beginning, Stouder had an impact, working side-by-side with Wood to protect Idaho’s 9-plus million acres of backcountry roadless lands in a home-grown Idaho way that is deeply entrenched in Idaho conservation today. After that victory, Stouder went on to work on the Clearwater Collaborative and a number of other issues facing Idaho conservationists. He officially retired in 2016 and he now spends all of his free time pursuing the fish and game that he helped.

1

2

3

4

Growth and change

- Innovation and conservation

- Playing the long game

- Off Road Vehicle and Sportsmen Ride Right

- Oregon and Arizona Mineral Withdrawals

- Overcoming congressional gridlock with public lands planning

- Working in state legislatures when Washington, DC, is broken

- The importance of national monuments

- Fight against selling state land

- Alaska Tongass National Forest

- Alaska Pebble Mine

- Utah Roadless

- Washington Steelhead fishing regulation changes

- Land and Water Conservation Fund

5