A steelhead sanctuary and two American legends

Franke and Jeanne Moore

He was 21, just a young kid from the deep woods and crystal rivers of western Oregon. Beside him were other young men just like him with similar hopes and dreams. Kids from the cities and farms, forests and rivers, deserts and canyons of America. Staying alive was a challenge. Staying sane was even harder.

When Frank Moore marched over the shattered hulk of a bridge that crossed Normandy’s Sélune River on a June day in 1944, he saw something that helped him cope with the war he was fighting: salmon. There, swimming beneath the bridge in the middle of a battlefield, was an Atlantic salmon, a living, moving miracle. Leaning against a nearby building was a fly rod.

Years later and back home safe in Oregon, Moore would recount that story, remembering how much he wanted to pick up that rod and cast to that fish, as he had cast to many salmon and steelhead on his native waters in the United States. That fish in war-torn Europe sharpened his focus, made him think of home and of his new bride, Jeanne, who was waiting for him on another river of salmon. He wanted to fish, sure, but he was on a mission to liberate France from the clutches of Nazi Germany and there would be no stopping to fish until the job was done.

One of the last surviving members of the D-Day Invasion, Frank served in the 453rd automatic weapons battalion of the Army Corps 83rd Infantry Division in World War II. He was part of a group of young men who not only landed on the beaches, but fought all the way to the Battle of the Bulge and end the war in the European Theatre.

No spey rod for Frank Moore. Few anglers throw as pretty a loop as Frank Moore, here at 90, on his beloved river.

Like many of his fellow soldiers in World War II, Frank Moore left a lot of his buddies behind on foreign soil. He will tell you that those left behind were the real heroes and that he was just lucky. He came back home. Back to western Oregon and back to his beloved young wife. They built a life, a family, a business, a reputation. The centerpiece of that life was a river: the North Umpqua and the business was the famous Steamboat Inn on the banks of that legendary steelhead stream.

Frank and Jeanne Moore are conservation and fishing legends on the famous North Umpqua River. Here, they are congratulated by Rep. Peter DeFazio.

Today, three-quarters of a century later, Frank is widely recognized as the dean of Northwestern steelhead fishing. He and his wife, Jeanne, are in their 90s and still find solace in the forest, the river and the fish that swim there. They have earned a living from the land and have stood up for good management of the river, the fish and the surrounding forests all of their lives. In the logging days of the 1970s and 80s, Frank and Jeanne were disturbed by what they were seeing from the rampant clear-cuts in western Oregon. Rivers were choked with silt from soil stripped of trees. Buffers around drainages were nonexistent. Steelhead and salmon returning from the sea found their spawning gravel buried in mud, changed, destroyed. Frank was instrumental in a documentary that showed on national television called Pass Creek and with that film and a projector, he flew in his own plane around the country, organizing anglers and others who cared about wild fish and wild rivers. In many ways, Frank was back on a battlefield again, Jeanne at his side. Now, many years after that battle and others, they are being recognized for their accomplishments and for a life dedicated to conservation of the country’s natural resources.

Since the 1940’s Frank Moore has fished the pools of the North Umpqua River guiding clients, fishing with famous people, family and friend.

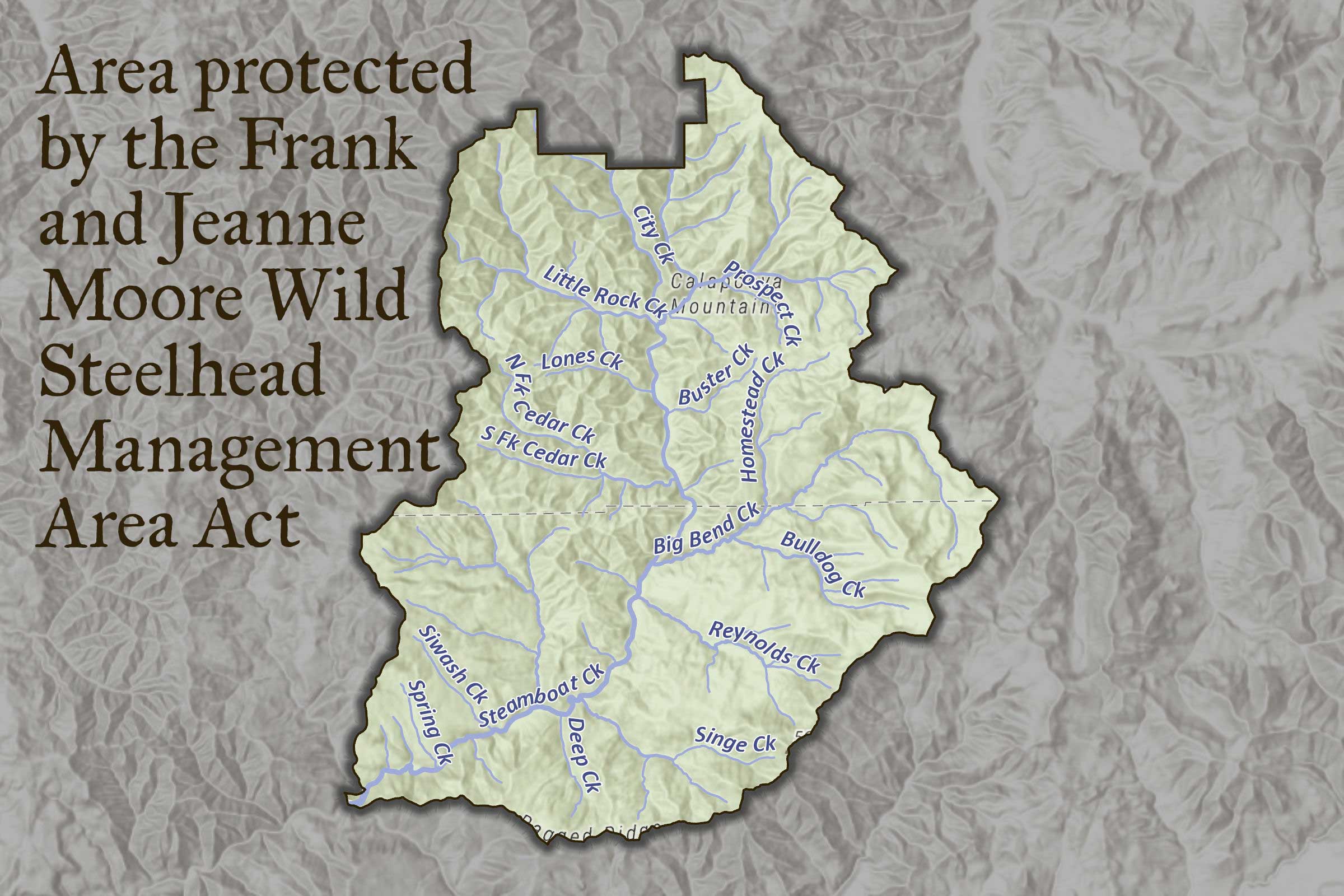

The Moores, of ldleyld Park, Ore., are the honorees of the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Sanctuary bill that protected 100,000 acres of critical habitat on the North Umpqua River. Serendipitously, Trout Unlimited’s Dean Finnerty was the organizer on the ground who helped make the bill a reality, but more importantly, Finnerty and his family were dear, long-term friends of the Moores.

In 2016, Frank, then 94, helped Trout Unlimited produce a couple of films about the act as well as the value of public lands in general. The day of film production, Frank and Dean got on the North Umpqua to be filmed by Trout Unlimited’s videographer. During the filming, Frank became very emotional and shared with Dean that he had just been thinking a few days before that he would never again have the opportunity to fish the famous steelhead pools of the river. Frank has fished these pools thousands of times since the 1940s guiding clients, fishing with famous people, family and friends. At 94, he did not feel confident wading out on the ledges to cast for steelhead in the notoriously difficult-to-wade North Umpqua. But because he and Dean needed to get the videographer some footage in support of Trout Unlimited’s public lands protection efforts, it gave the men the opportunity to get back out on the water to do some fishing. Those there that day, including Frank himself, surmised that Frank would only have the strength to wade out and fish one pool. But after Frank got down in the water and started fishing, it gave him the strength, determination and stamina to keep fishing. Frank, with Dean at his side, fished five or six pools over several hours.

Steamboat Creek

“I often wonder when I’m getting to do something so special if I’ll ever get the chance to do or see it again?” remembered Finnerty. “Life changes in inches and seconds and I know how easy it is to take it all for granted. That’s kind of how it felt for me and Frank that day. But the river restored him, gave him the energy to talk about how important public land and the North Umpqua is.”

For Finnerty, a long-time friend of the Moores, the bill to honor them was personal. The Moores had been incredibly influential with the entire Finnerty clan of five boys and Dean’s wife, Brenda.

Trout Unlimited was integral to the 2019 passage of the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Management Area Act, which protects over 100,000 acres of vital fish habitat. Trout Unlimited is a trusted, savvy organization and their members know how to get things done.

—Congressman Peter DeFazio, D, Oregon

The Moores were role models for the Finnertys in many ways: how they loved one another, how they cared so deeply for other people, the land and water. The two families had laughed together, cried together, broken bread together and fished together. So Dean started gathering a force to be reckoned with: veterans’ groups, industry officials, local leaders, conservation groups, bi-partisan politicians. Like a gathering storm on the horizon, the collective thunder was heard by Oregon leaders like Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley and Reps. Peter DeFazio and Kurt Schrader. DeFazio, himself an avid fly-fisherman, even fished with Frank and Dean on the North Umpqua.

The Frank and Jeanne Moore steelhead sanctuary protects some of the Pacific Coast’s most fabled waters.

Yet even with vast support across the state of Oregon, the bill to honor two legitimate American heroes fell short in the 115th Congress. Undeterred, Dean and the hundreds of others who supported the bill were back for the 116th Congress. This time, in February 2019, the Frank and Jeanne Moore Wild Steelhead Sanctuary Act was passed as part of the legendary John D. Dingell Jr., Conservation, Management and Recreation Act. As a result, some 100,000 acres of national forest are forever protected for wild steelhead on the famed North Umpqua River in Oregon.

TROUT PEOPLE

Tasha Sorensen

Sixteen. For a lot of teenagers, that’s a milestone that encompasses many aspects of a young life. For Tasha Sorensen, that was the age she flew her first solo mission for her pilot’s license. Most of her peers were just learning to drive and Tasha was flying an airplane over the sagebrush ocean that surrounded her hometown of Yerington, Nevada. Driving? Heck she’d been driving since 10, maybe even younger, and not just a Honda Civic with a favorite CD blaring and an automatic transmission, but steering big stick-shift fuel tankers loaded with aviation fuel out to airplanes on the tarmac 80 miles southeast of Reno.

Sorensen’s family built their business out of nothing but sagebrush and creosote into a going concern that included a restaurant where pilots could eat a good meal and all the necessary infrastructure for a successful aviation business. In her very little free time, Sorensen would go down near the banks of the Walker River where a den of foxes kept her entertained. She eventually made those foxes into friends—they ate restaurant scraps out of her hand—and went on to a career in wildlife biology, inspired not only by the canines, but by taking survey flights as a child observer with wildlife biologists while her dad flew the plane.

There followed a career as a wildlife and fisheries biologist working across western states on any number of wildlife and fisheries challenges of the day, from chronic wasting disease to studying how endangered chubs moved up and down the Colorado River system. For the latter job, she told the interviewer, “You better hire me because I can fix all of your jet boats, I can maintain all of your equipment here and extend your sampling season.”

Later on, she was working on a crew doing the first live field testing of mule deer for chronic wasting disease when she was knocked off a cliff by a big buck mule deer. The deer, which was recovering from the effects of anesthesia, landed on top of Sorensen and bounded away unhurt, but that was not the case for his human landing pad. Although knocked out for a time, she walked out of the field but she had torn her MCL and ACL and to this day packs titanium around in her left leg. That accident forced her ultimately out of the field and eventually to Trout Unlimited.

At TU, Sorensen was first a field organizer in Wyoming. Now she is the lead expert in energy issues across the West for the organization. “I remember seeing the job posting about cold, clean water and I thought, ‘Hey, I like cold, clean water,’ so I applied,” said Sorensen. “It was the perfect fit. Yerington was a copper town and growing up near an open pit mine, I’ve seen many families decimated by unexplained illnesses in the valley so I knew how important clean water is. I’m so blessed I’m in a job where I feel like I can make a difference. Our ground game with oil and gas and water is so important, and then to connect all of that to make good policy when it comes to extraction yet maintaining high quality fisheries, it’s where the rubber meets the road for me.”

1

2

3

4

Growth and change

- Innovation and conservation

- Playing the long game

- Off Road Vehicle and Sportsmen Ride Right

- Oregon and Arizona Mineral Withdrawals

- Overcoming congressional gridlock with public lands planning

- Working in state legislatures when Washington, DC, is broken

- The importance of national monuments

- Fight against selling state land

- Alaska Tongass National Forest

- Alaska Pebble Mine

- Utah Roadless

- Washington Steelhead fishing regulation changes

- Land and Water Conservation Fund

5