The adventure and mystery

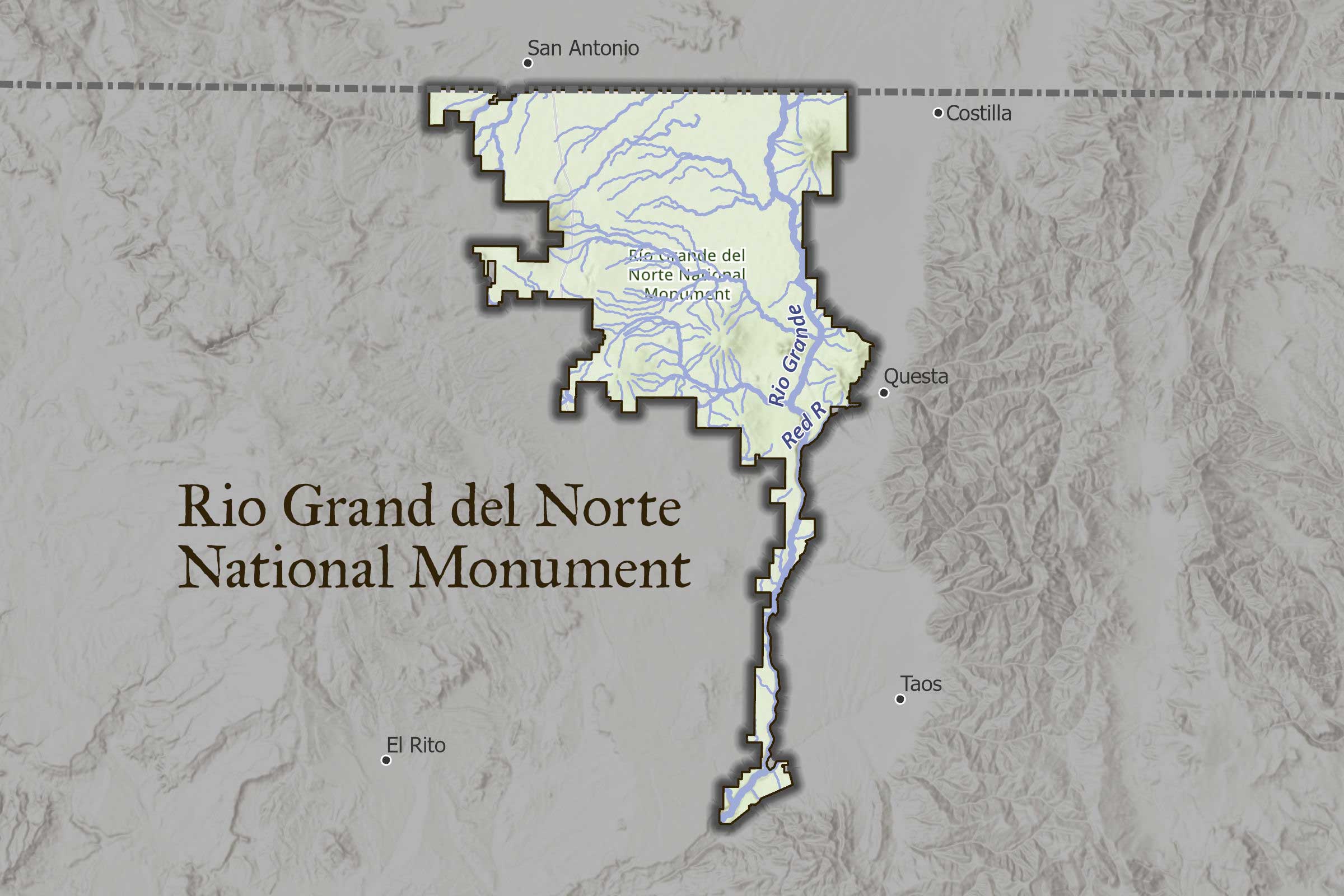

Rio Grande del Norte National Monument

The Red River crashes into the Rio Grande deep into a gorge hundreds of feet below the canyon rim, the merging of two great western rivers hidden from sight.

Eight hundred feet above, piñon and juniper scatter across a flat sagebrush mesa that looks more ocean than land. To the east, the Sangre De Cristo Mountains loom.

The raw, windswept rim of the great canyon of the Rio Grande is a place to pause.

But walk on. The gorge stretches out before you, a long rent in the earth with walls hundreds of feet high and appearing impossible to scale even for those with climbing shoes and ropes. Far below, the Rio Grande appears to be a languid ribbon of off-color water draining slowly south. Up close, the river is not lazy at all, but a rushing torrent. What appear to be pebbles from up top are in fact boulders, some as big as cars or small houses.

The Pueblo people of northern New Mexico called the river “P’Osoge” (Big River). Later, Spanish conquistadors would call it El Río Grande del Norte. In this section of the river west of Taos, the Rio Grande is often just called “the Gorge.”

From the Wild River’s Recreation Area on the La Junta trail, it’s a mile to the bottom. A damn steep mile that will punish your knees on the way down and everything else on the way back up.

Rio Grande cutthroat are the native trout of this region.

The Gorge is the kind of wild place that was spared from roads and development by geologic luck-of-the draw. Some 30 million years ago, the earth’s tectonic plates started drifting, stretching apart an area of land from Colorado to Texas and south into Mexico. The shift opened a line from Leadville, Colo., to Chihuahua, Mexico into a rift valley. That rift valley captured streams and rivers, rerouting them and gathering them up into the 1,800 mile-long Rio Grande. In other words, the river did not create the gorge; the gorge created the river.

The Rio Grande drains a stunning western landscape en route to the sea.

In 2009, U.S. Sen. Jeff Bingaman introduced legislation to protect the gorge as a National Conservation Area with companion legislation in the house by U.S. Reps. Ben Ray Lujan and Martin Heinrich. The bill was introduced in both houses again in 2011 and 2013. Unfortunately, Congress was unable or unwilling to act even though the bill had broad support from locals, hunter and anglers, the New Mexico congressional delegation, the county, and the governor.

Ultimately, Congress never could get its act together to vote on Rio Grande del Norte legislation. So, Trout Unlimited and many others had a plan B: Ask the President of the United States to designate the landscape a national monument where our hunting and fishing heritage would be forever protected. Monument designation would ensure that hunting and fishing—along with tourism like hiking and backpacking—would be the primary, sustainable and lasting uses, not one-time, often-damaging extraction of oil and gas.

Fortunately, President Obama declared Rio Grande del Norte a National Monument in 2013, using his authority under the Antiquities Act to protect the Rio Grande Gorge for future anglers. In 2017, Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-NM and Sen. Tom Udall, D-NM, successfully passed the Cerro del Yuta and Rio San Antonio Wilderness Act, and designated the Cerro del Yuta Wilderness and Rio San Antonio Wilderness within the Río Grande del Norte National Monument.

There is nothing I love more than casting a dry fly on a remote stretch of water in the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument. I am deeply grateful for the work that Trout Unlimited has done to make that kind of experience possible. Trout Unlimited has demonstrated how to successfully organize anglers and hunters and shown that standing up for protecting our public lands and waters, restoring healthy watersheds and expanding public access can be something all of us, regardless of our political party, can get behind.

—U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, Democrat, New Mexico

From the bottom there’s only two ways out: the river or up.

A similar story can be told for Browns Canyon National Monument in Colorado, Berryessa Snow Mountain National Monument in California and Organ Mountains – Desert Peaks in New Mexico.

All of these public lands that are now protected as national monuments were first legislative proposals – legislation that Congress failed to pass.

It is the pattern that goes as far back as 1911 and the designation of 13,884 acres of public land as the Colorado National Monument. With legislation languishing in Congress, U.S. Rep. Edward T. Taylor wrote President Taft urging him to create a national monument, explaining that, “The people have been trying to have it set aside as a national park and Sen. Guggenheim and I have had bills in Congress for that purpose. But Congress does not seem to be disposed to create national parks…”

From some of America’s first national monuments, to some of our most recent, these designations have occurred in response to Congress failing to act on legislation despite overwhelming local support. When Congress is unable to take action on conservation initiatives, the Antiquities Act provides a vehicle to see these proposals through to fruition.

Even though I no longer live in New Mexico, the Rio Grande Gorge is part of my story. It is a place that formed me not only as a fly angler, but as a conservationist and as a man, a husband and a father. It is a place that deserves to remain. A place where future generations can visit to catch fish and get skunked. A place to explore and hike and sweat and learn how to hang a pack out of reach of bears and wade the cold, swift water of an iconic river.

Because of the Antiquities Act, the Rio Grande does – and will – remain.

—Greg McReynolds, Pocatello, Idaho, formerly of Albuquerque, New Mexico.

TROUT PEOPLE

Gregg Flores

Outdoors and family have always been intertwined for Gregg Flores. A child of the West whose New Mexico roots run deep, Flores spends his free time with his family out in the wilds of the Land of Enchantment. His Grandpa Flores introduced him to hunting, while his parents and Grandpa and Grandma Chavez loaded up their cab-over camper every summer and introduced him to New Mexico’s state parks, national forests, and variety of public lands, always with fishing gear along.

“We did a lot of exploring mostly across Northern and Central New Mexico,” said Flores. Starting out, he fished more conventional tackle, but in his teens, he started to transition to fly fishing. Trout Unlimited then became a big influence. “As a teenager, I honestly wasn’t aware of what Trout Unlimited did, but over time I met anglers and guides involved with TU. It became evident that Trout Unlimited was active throughout the state of New Mexico. Eventually, I realized the resource needed to be cared for and protected, not just used, and I wanted to do my part.”

Flores did some guiding as he moved into the fly fishing industry, but in 2013, he started Where The River Runs, (WTRR pronounced “WATER”) www.wheretheriverruns.com . The company, which specializes in video-based online fly fishing education and the creation of short outdoor films, started as a way to share photos of adventures and has evolved into its current form. It is a member of the Trout Unlimited business family, with Flores’ film work supporting any number of conservation projects across New Mexico, while helping Trout Unlimited chapters in several New Mexico locations. “New Mexico is a state steeped in culture and tradition and our people have some of the most beautiful stories you’ll ever encounter. My goal with the story-telling aspect of WTRR is to use film and photography to capture those stories and share them with the world. You’ll notice that the vast majority of my stories center around our local people and families, our guides, fly shop owners, fly–tiers, rod builders, and hunters. Their stories are so important. Not just to me but New Mexicans in general. Their stories are something people can relate to but I think story-telling also encourages us to be more understanding and caring. For the people, yes, but also for the resource,” said Flores, who has spent a great deal of time on the Rio Grande.

Flores helped to tell the story of the Rio Grande Gorge through WTRR’s filmmaking, which in turn helps others understand the vital hunting and fishing resource that was protected when President Obama designated the Rio Grande Del Norte National Monument. Part of the filming included an effort that stocked pure Rio Grande Cutthroat trout in the gorge. “It’s an incredibly special experience to see native trout going into their native river. The Rio Grande Cutthroat is New Mexico’s state fish and until recently, catching one in its namesake river was simply impossible. Thanks to efforts by Trout Unlimited and other like-minded organizations, you actually have a chance at it now. It’s special. Especially for New Mexico anglers.”

Meanwhile, as the father of three children—a girl and two boys (and another on the way)—Flores is passing on the fishing and outdoors tradition just as was passed on to him. Quite often, they find themselves in the mountains with family, enjoying the great American public land and family experience. “It would be strange if we weren’t out there enjoying it. It’s a way of life for us. It’s not just recreation. It’s essential. I do understand, though, the massive impact Covid has had on everyone’s ability to get out in 2020 but I do hope that through our films and online fly fishing education platform we are helping people enjoy it from afar.”

1

2

3

4

Growth and change

- Innovation and conservation

- Playing the long game

- Off Road Vehicle and Sportsmen Ride Right

- Oregon and Arizona Mineral Withdrawals

- Overcoming congressional gridlock with public lands planning

- Working in state legislatures when Washington, DC, is broken

- The importance of national monuments

- Fight against selling state land

- Alaska Tongass National Forest

- Alaska Pebble Mine

- Utah Roadless

- Washington Steelhead fishing regulation changes

- Land and Water Conservation Fund

5